One of the myths told about courting elephants, is that the bull has to knock down several trees to win the heart of the desired female. If only there was a way to talk them out of it, joked Agnes Masika, KWS assistant director of community services, then the quest for environmental conservation in park areas would be much easier.

Instead, the elephants compound the problem by debarking Acacia trees – the more common type in the Amboseli – chewing the bark for a juice they just can never seem to get enough of.

Both scenarios explain the spectacle of felled, whole, debarked trees that now constitute much of the landscape in Amboseli.

“I was here in 1955,” says Swedish conservationist Sigvard Berggren who remembers the impassable jungle of trees and bush.

Over the years, the Amboseli he knew has turned into a moonscape of dry, arid land with barely a tree inside the main park area.

As the deforestation became more apparent, scientists also noticed a fluctuation in the area’s water table, creating huge swamps that at times cover the entire land surface or sink so low that nothing can grow.

With much of the ground gradually shaven of trees and bushes, what immediately strikes the eye is a vast hard, dusty terrain, covered with what appears like remnants of a volcanic explosion with the spectacle of dead trees as the only testament to its past.

At first scientists could not agree on the cause of this monolithic degradation.

Most blamed it on the water levels, says the KWS Director, Dr. David Western, with the theory that the waterlog in wet seasons swept away seeds before they could germinate while the dry season simply ate up whatever was on the ground.

But after years of watching the weather patterns, Dr. Western saw little connection between the water levels and the environmental degradation.

His attention turned to wildlife and he was soon convinced that elephants were the sole cause of the damage in the park.

To prove this point he put up wires on isolated selected portions of land. The wires were high enough to allow the smaller animal species entry and only kept out the elephants.

In time, vegetation started emerging and the characteristic bushes and Acacia trees flourished again.

He also noted that the elephants’ fear of people, more so with the increased poaching for ivory, drove them away from areas inhabitated by the Maasai.

He took his findings to other researchers and officials in the Ministry of Tourism but was surprised by the rejection at government level.

When the Kenya Wildlife Service was formed and given authority on all matters related to wildlife and park management, Dr. Western took his case there too, but in vain.

As it turned out the problem with his now proven theory was one of timing. Coming in the early 1980s, the Government’s concern was to fight the poaching that was then rampant in most national parks.

Says Dr. Western, “It could be that my theory blaming elephants for destroying their habitat was being viewed in conflict with the official theory that poachers were destroying wildlife and the government, then working to rally support for its anti-poaching campaign would not dare do anything to deflect attention from the poaching menace.”

He sees the logic, but feels it did not justify the damage that has resulted.

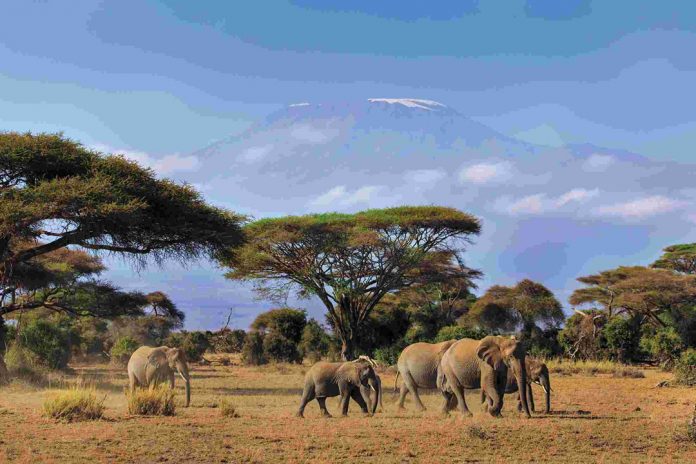

Elephants in a destroyed portion of the park.

Poaching was a problem, he admits, but the emphasis should have been on solving the issues in their entirety, not at the expense of the other. Now there is no poaching but the destruction of the habitat has left elephants and other species without ample feeding ground for their survival. With their migration trails blocked, and crowded out by human settlement the elephants have turned the Amboseli legend into a dusty, barren desert.

With an elephant population of almost 1,000, Amboseli is choking and hard-pressed for pasture, yet KWS asserts that the park and surrounding ranches can comfortably accommodate 5,000 jumbos.

But it is unlikely that the land would be rehabilitated soon enough to serve the current number and scientists are already looking at other options.

One of them, Sigvard Berggen, sees encroachment of the parks by rising human and livestock population as a major threat to elephants in the region.

“There would have to be a way to stop this competition for space between wildlife and communities in such regions,” said the Swedish researcher who works for the Swedish Amboseli Association . Indeed, the commercial success of the group ranches compounds the problem and as the communities’ incomes improve the tendency to invest in cattle can only raise their numbers.

The other focus has been on the elephants with some scientist floating the idea of introducing infertility drugs to stop further increases – at least for the time being.

But Dr. Western would rather exhaust other avenues. The issue of cattle does not even seem to bother him and indeed he considers them a balancing factor in the afforestation programme.

Mount Kilimanjaro as seen from Amboseli National Park.

One of the biggest effects from poaching, he says, was that elephants left the migration trail to seek refuge in safer areas which the KWS director believes, deprived the habitat of the cycle that allows grown land to recover its vegetation.

With poaching now wiped out, his objective is to persuade elephants back to the migration trails which would allow recovery of the present habitat.

One of the considered ways, is to lay elephant dung along the old trails and an experiment with rhino has shown that the smell of its own dung offers some kind of solace and reduces an animal’s resistance to new land.

The alternative is to move them to other parks and indications are that Tsavo could be a likely future home for the jumbos.

It is not an idea Dr. Western is comfortable with as he fears that it could interfere with nature’s way and Amboseli’s character.

For as tourists freely admit, you won’t see wild elephants closer anywhere else in the world.

JOHN KARIUKI

reporting for Safarimate